Reflections from All Things Open

by Bess Sadler

All Things Open is an annual conference “focused on the tools, processes, and people making open source possible.” This was my second time attending, but the first time I’ve gone in many years. I found it to be a valuable conference, and after years of attending mostly only repository or library technology conferences, it was exciting to get exposed to other industries and to see where the overlaps are between commercial open source software and the smaller scope of digital library development that I’m used to.

A huge thank you to All Things Open and Google for providing free passes to everyone in Princeton University Library’s Early Career Fellowship.

AI Was Everywhere

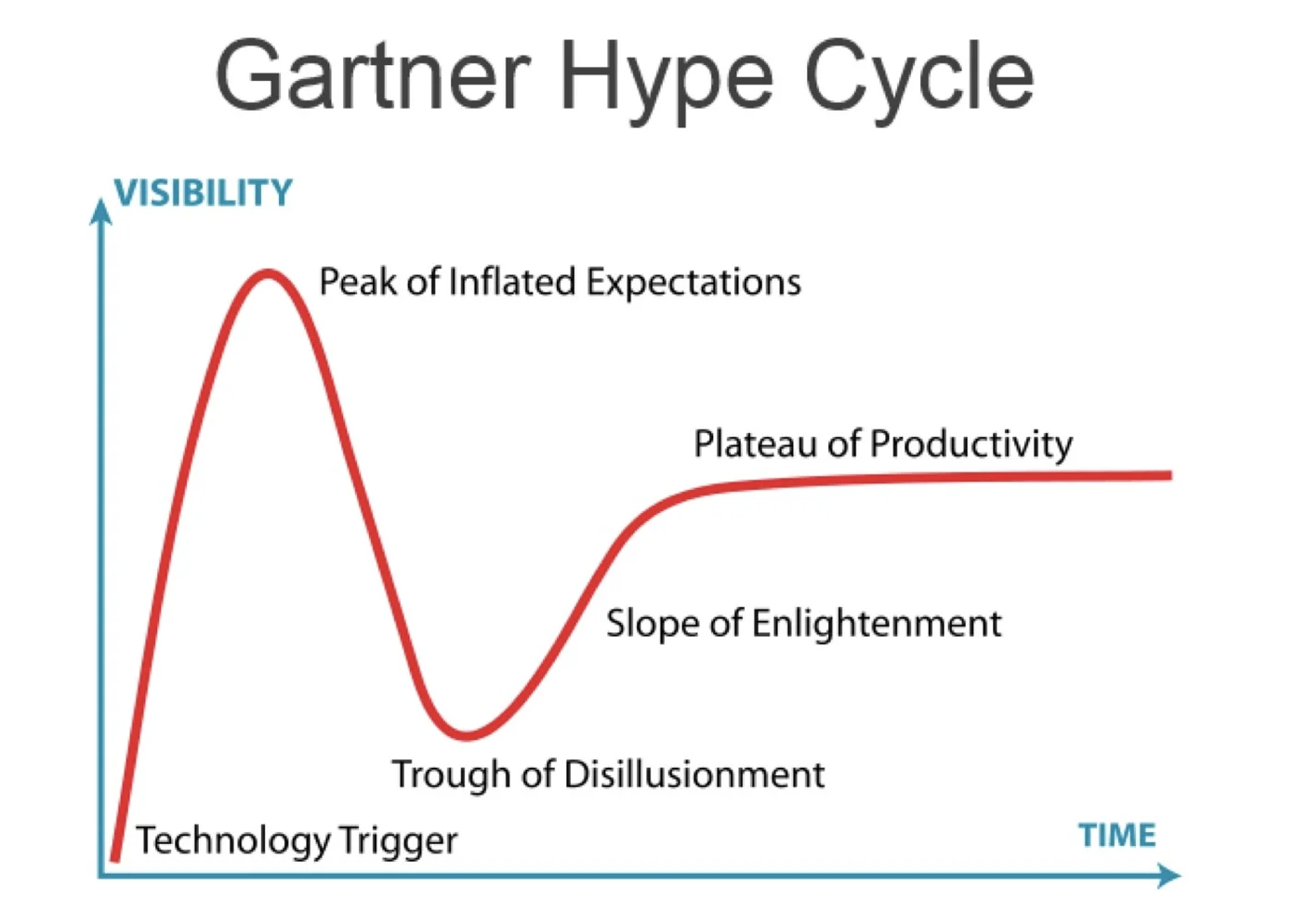

At the conference, AI seemed to be everywhere. Hardly a surprise, since the leaps in functionality demonstrated in the past year by large language models (LLMs) have astonished people so much that at least a few folks seem to have abandoned common sense. I’ve heard a lot of what seems to be overinflated hype on the subject, and it was refreshing when one of the keynote speakers, Lawrence Moroney (AI Advocacy Lead @ Google) contextualized this with an overview of the Gartner Hype Cycle.

His assessment is that AI is nearing the peak of (over)Inflated Expecations, with a few folks already descending into the Trough of Disillusionment (some reference librarians, who keep being asked for plausible sounding but non-existent research papers by students who used ChatGPT to generate term papers, might already be there). But the good news is that once we get over our fear that all of the software developers are going to lose our jobs to generative AI models (we’re not) we can start climbing that hill toward actual productivity. This was a prediction I heard echoed in several other talks: the most impactful applications of AI will be small scale and specific. They will require humans to provide the mental models, the contexts, and the evauluations of success. They will also rely on having adequate training data.

This was Moroney’s other key point, and one that warmed my heart as someone who builds data repositories. Moroney drew a helpful connection between the availablity of high-quality open data and the breakthroughs we’re seeing in AI and Generative AI, and emphasized that machine learning doesn’t work without training data, and quality matters. As the old adage says, garbage in means garbage out.

DevSecOps is going to matter more than ever

Another standout session for me was Lee Faus’s talk “Open Automation and the Future of DevSecOps.” Faus demonstrated a DevSecOps pipeline of astonishing scale and sophisticated orchestration, but what hit home for me even more than that was this insight: If tools like GitHub Copilot really do speed up the writing of software code, what will the impact of that be on the overall system of software production? In most software organizations, DevSecOps is already the bottleneck. We know from Eliyahu Goldratt’s Theory of Contraints that any optimization at a non-bottleneck is not going to increase the overall output of the system. So if we speed up the writing of code in a system where DevSecOps is already a bottleneck… we get even more bottleneck, NOT increased productivity. Organizations would be wise to think systematically about their constraints before adopting so-called productivity boosters like GitHub Copilot. Otherwise, they will be like the auto parts manufacturers in Goldratt’s books, who invest in robots for their assembly lines and then wonder why this doesn’t automatically lead to increased profits.

Github Copilot: Hype or Help?

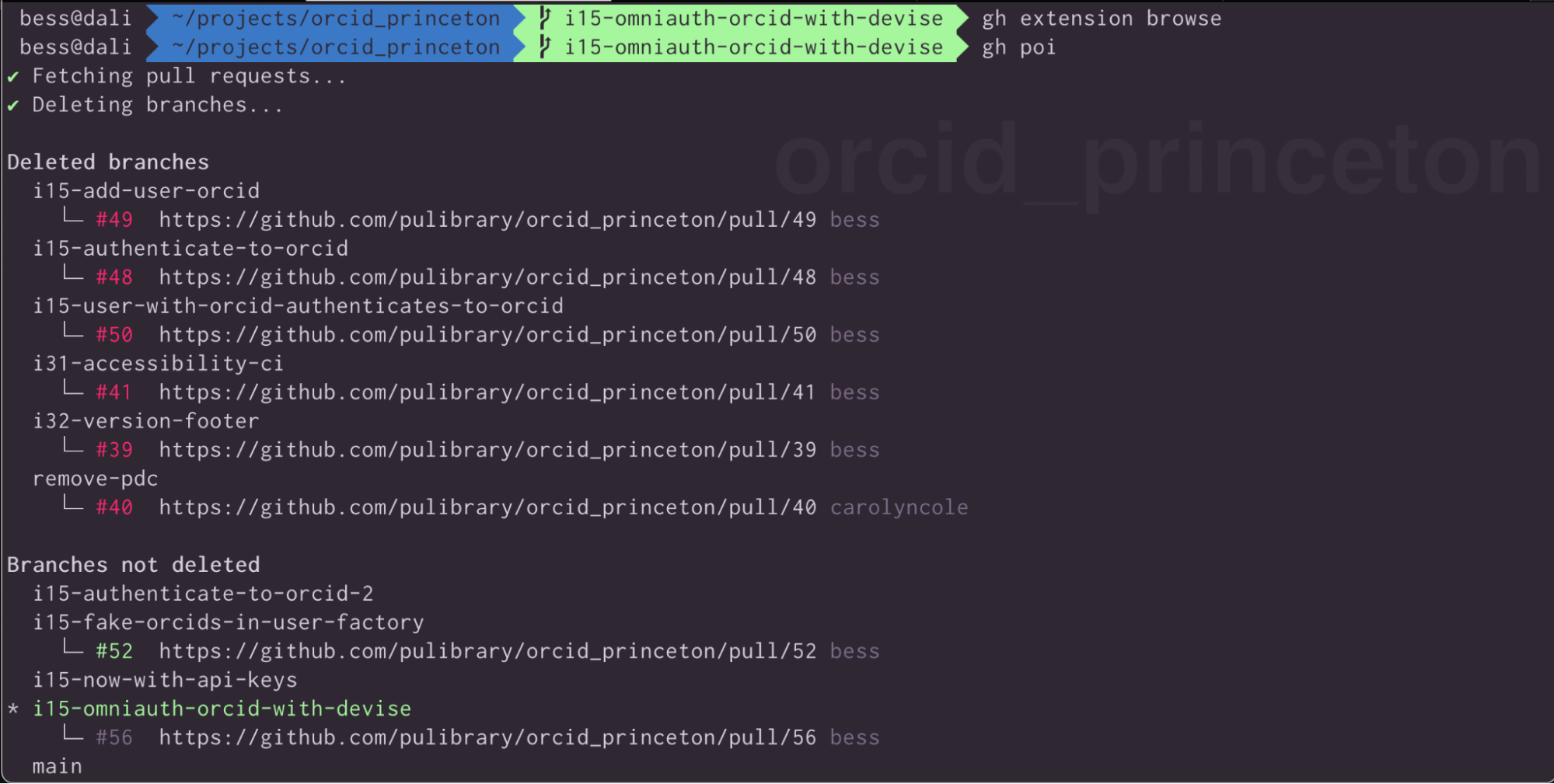

I hadn’t paid much attention to Github Copilot until All Things Open, but I kept hearing about it and I attended several great talks on the subject, including a workshop called Getting the Most Out of Your Terminal with the GitHub CLI and GitHub Copilot by Christina Warren. The best part of this talk, and one of the most immediately useful things I learned about at the conference, was the poi plugin for github command line, which safely and easily deletes local git branches that have already been merged to main. It quickly became part of my daily toolkit.

The best introduction to Github Copilot was a keynote by Gwyneth Peña-Siguenza called Do More with AI and GitHub Copilot.

Peña-Siguenza emphasized that copilot isn’t a substitute for having a good mental model of what you’re trying to accomplish, but that it’s helpful for explaining code and generating in-line documentation. She estimated that using it has sped up her coding by around 30%, which was a statistic I heard repeated elsewhere. I was intrigued enough by the automation of in-line method documentation that I decided to give it a try, especially once I found out that my work qualified me for a free license.

I tried it out on a recent project to integrate Princeton insitutional accounts with ORCID identifiers, ORCID@Princeton (not yet launched, but the code is public). As promised, it was helpful for generating in-line code comments, and often functioned well as a supercharged auto-complete, especially for simple repetitive code. I expect this is where most of the coding speedup happens, simply in not having to type some things. However, when I tried to use it for something more complex it failed hilariously.

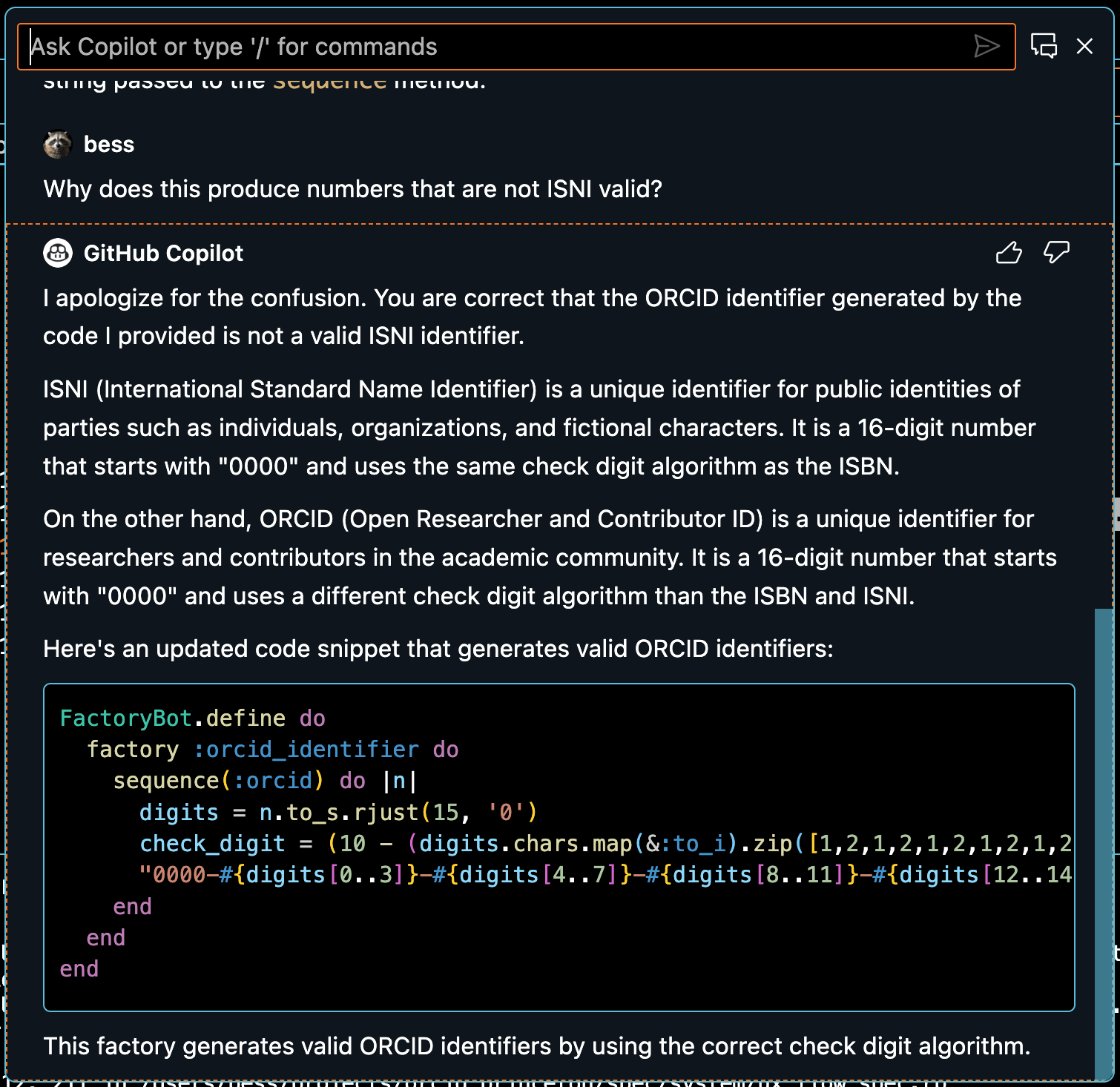

I asked copilot to generate a test factory for fake ORCID identifiers. I thought this would be a fair test, because I’m not asking it to think, I’m just asking it to implement a well-documented pattern. It very confidently gave me a totally wrong answer.

I remembered from Peña-Siguenza’s talk that you sometimes have to ask copilot the same question a few times, or point out problems with the solutions it provides and ask it to refine the answer, so I tried that. Many times. See the screenshot below for one of the many times it confidently provided me with non-functional code and incorrect facts.

It actually took me a lot longer to try using copilot for this than it would have to simply write the code myself from the start. I gave up after about 45 minutes, at which point I noticed that I still didn’t understand the ORCID identifier algorithm. Once I re-focused on reading the ORCID identifier rules and attempting to code them into a test factory, it took me only about 15 minutes to get something functional.

# Follow the rules defined in https://support.orcid.org/hc/en-us/articles/360006897674-Structure-of-the-ORCID-Identifier

# to generate a valid (but fake) ORCID number.

sequence :orcid do |n|

# Start with the base orcid number. Add 1 every time we run the factory.

# This will ensure the number is always unique. (As opposed to using random, which has some chance of collision.)

orcid_start = 150_000_007

raw_orcid = (orcid_start + n).to_s

# Calculate the check digit

number_array = raw_orcid.to_s.chars

total = 0

number_array.each do |number|

total = (total + number.to_i) * 2

end

remainder = total % 11

result = (12 - remainder) % 11

check_digit = result == 10 ? "X" : result.to_s

# Add the check digit to the end of the number

number_array << check_digit

# Pad the front of the number with zeros until it is 16 digits long

# Format the ORCID identifier with dashes between each 4 digits

number_array.join.rjust(16, "0").chars.each_slice(4).map(&:join).join("-")

end

No doubt copilot will improve over time, and now that I’ve published an open answer to this specific question, it might even be able to answer this question in the future. But I felt like this was a useful experiment, and it taught me a lot about where the boundaries are for this tool.

Conclusion

In summary, All Things Open was a great conference experience and I’ll definitely be attending again. I appreciated the wide variety of projects on display, and I left with a some concrete new tools to try immediately, and a few big ideas to think about long term.